- The City of Portland granted a building permit for a 12-story cross-laminated timber (CLT) tower this year.

- SOM developed a “concrete-jointed timber frame” system which they say could be used to construct a 42-story tower.

- The first large CLT building in Massachusetts opened at UMass Amherst this year, and it uses an innovative wood-concrete composite floor system (Figure 1).

Sustainability Guidelines

Sustainability Guidelines Thermal Bridging Solutions in MSC

Thermal Bridging Solutions in MSC Carbon Working Group White Paper

Carbon Working Group White Paper Top 10 FAQs Answered

Top 10 FAQs Answered

Sustainability Guidelines for the Structural Engineer

Learn strategies for integrating sustainability into structural design. More

Thermal Bridging Solutions in MSC

April 2012 Issue of MSC: "Thermal Bridging Solutions: Minimizing Structural Steel's Impact on Building Envelope Energy Transfer." More

Carbon Working Group White Paper

Structures and Carbon: How Materials Affect the Climate. More info.

Top 10 Structural Sustainability FAQs

The LCA working group provides answers to 10 FAQs asked by conscientious structural engineers, more

Carbon Group Post 5: Wood

Categories :

Carbon . Climate Change . Features . wood . Working Groups

Project: Thermal Break Strategies for Cladding Systems in Building Structures

Categories :

Check out this developing project!

Carbon Group Post 4: Do you know how to achieve a carbon-efficient steel-framed building? Your fabricator does.

Categories :

Carbon . Climate Change . Features . steel . Working Groups

Carbon Group Post 3: Example Demonstrating How SCMs Can Reduce Embodied Impacts of a Concrete Building

Categories :

Carbon . Climate Change . concrete . Features . Materials . SCMs . Working Groups

Concrete

Element

|

Specified

Compressive Strength (psi)

|

Portland

Cement (lbs/yd3)

|

Slag

(lbs/yd3)

|

Fly Ash

(lbs/yd3)

|

SCM

content

|

Mat

Foundation

|

6000

|

782

|

119

|

82

|

20%

|

Basement

Walls

|

5000

|

741

|

112

|

78

|

20%

|

Floors

B2-1

|

5000

|

741

|

112

|

78

|

20%

|

Floors

2-18

|

5000

|

741

|

112

|

78

|

20%

|

Shear

Walls

|

6000

|

782

|

119

|

82

|

20%

|

Columns

|

8000

|

967

|

147

|

102

|

20%

|

Concrete

Element

|

Specified

Compressive Strength (psi)

|

Portland

Cement (lbs/yd3)

|

Slag

(lbs/yd3)

|

Fly Ash

(lbs/yd3)

|

SCM

Content

|

Mat

Foundation

|

6000 psi

|

256

|

342

|

256

|

70%

|

Basement

Walls

|

5000 psi

|

242

|

323

|

242

|

70%

|

Floors

B2-1

|

5000 psi

|

512

|

0

|

341

|

40%

|

Floors

2-18

|

5000 psi

|

581

|

0

|

249

|

30%

|

Shear

Walls

|

6000 psi

|

427

|

256

|

171

|

50%

|

Columns

|

8000 psi

|

503

|

302

|

201

|

50%

|

Carbon Group Post 2: What About the Data?

Categories :

Carbon . Climate Change . Data . Features . Working Groups

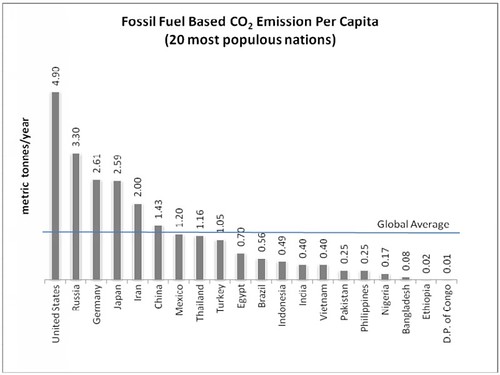

Carbon Group Post 1: Why Climate Change Matters

Categories :

Carbon . Climate Change . Features . Materials . Working Groups